Key Takeaways

- Process selection is more decisive than technology choice. Automating the wrong workflow undermines credibility, regardless of platform strength.

- Value isn’t just cost savings. Regulatory compliance, scalability, cycle-time improvements, and employee morale can deliver more impact than labor reduction alone.

- Effort is frequently underestimated. Hidden complexity comes from variability, exception handling, legacy systems, and political ownership issues.

- The framework is a guide, not a verdict. A value-to-effort matrix structures the conversation, but leadership judgment and strategic alignment matter more than rigid scoring.

- Trust-building trumps perfect math. Sometimes the best process to start with is the one that proves automation works, not the one with the highest “calculated” ROI.

Automation projects often fail not because of the technology but because of the process selection. Teams chase shiny use cases, spend months configuring bots, and end up automating something that either doesn’t move the business needle or collapses under its own complexity. The challenge is universal: with hundreds of candidate workflows in any enterprise, which ones deserve attention first?

That’s where the value-to-effort model comes in. It’s not perfect—no framework is—but it’s pragmatic. It forces you to weigh potential benefits against the difficulty of execution. The trick, though, lies in how you define both “value” and “effort.” Those terms sound obvious until you try to apply them in the messy reality of legacy systems, cross-departmental ownership, and shifting business priorities.

Also read: The Evolution of Process Automation: From Bots to Self-Healing Agents

Why Process Prioritization Matters More Than Tech Choice

You could buy the best RPA platform on the market, stack it with AI, and still fail if you pick the wrong use case. I’ve seen it happen in a manufacturing client: leadership insisted on automating an exotic reporting process because it “looked impressive.” Six months later, the bot saved three analysts about two hours per week. Nobody cared. Meanwhile, invoice processing—dull but impactful—kept clogging up their finance team.

Process prioritization determines whether automation is seen as a toy project or a serious capability. It’s the difference between CFOs asking for more funding or cutting the program altogether.

The Value-to-Effort Model: Simple but Hard to Apply

At its core, the model is a 2×2 grid:

- High value, low effort: quick wins—your first targets.

- High value, high effort: strategic bets—worth it, but not right away.

- Low value, low effort: fillers—sometimes useful for training teams or demonstrating success.

- Low value, high effort: avoid at all costs.

It looks straightforward. The difficulty is that “value” and “effort” mean different things depending on context. For example, effort for IT might mean the number of integrations; effort for business might mean the number of approvals required before making changes. Misalignment on definitions leads to wasted cycles.

What “Value” Really Means in Automation

Most teams default to cost savings when measuring value. That’s valid but incomplete. A narrow focus on labor reduction makes you blind to processes that improve compliance, customer experience, or decision speed.

Some dimensions of value found useful:

- Financial impact: cost savings, reduced rework, or better cash flow. Obvious, but quantify it properly. A “$1M opportunity” usually shrinks when you account for variability and exceptions.

- Risk and compliance: automating regulatory checks may not reduce headcount, but it prevents fines that could dwarf any savings.

- Cycle-time improvement: shortening a quote-to-cash step by two days may generate more revenue than cutting an FTE in HR.

- Scalability: processes that buckle under growth (e.g., KYC checks in banking) carry hidden value because automation prevents bottlenecks.

- Employee morale: not fluffy at all. Taking away mind-numbing copy-paste tasks reduces turnover, which has real costs.

A practical example: A pharma client weighed automating document formatting for regulatory submissions. The labor savings looked modest. But the value skyrocketed once they factored in “time-to-approval” improvements with the FDA—accelerating product launches by even a week meant millions in revenue.

How to Gauge Effort

Effort is even trickier. Teams underestimate it constantly. What looks simple—“just grab this data from SAP and paste it into a portal”—turns into a six-month slog once you hit system restrictions, missing documentation, and business resistance.

Factors to consider:

- Process variability: Are the steps truly standardized, or does every region handle them differently? High variability = high effort.

- System landscape: Legacy green screens, Citrix environments, and tightly controlled SaaS apps all raise effort dramatically.

- Exception handling: The “happy path” may be 70% of cases, but the 30% exceptions drive most of the complexity.

- Change frequency: Automating something that changes every quarter means endless rework.

- Stakeholder alignment: Don’t ignore politics. If three departments fight over “ownership,” the governance effort alone is significant.

- Data quality: Bad inputs = fragile automation. Cleaning data often takes more time than building the bot.

Here’s a misstep noticed too many times: companies try to automate vendor onboarding without realizing procurement, finance, and compliance all run slightly different sub-processes. The result? Either build an overly complicated bot or create three parallel automations that never scale.

Building a Scoring Mechanism

The temptation is to turn value and effort into 50-question surveys, weighted formulas, and complex spreadsheets. But if it takes more time to assess a process than to automate it, you’ve gone too far.

A balanced approach:

- Assign a value score (1–5) across the key dimensions: cost, compliance, revenue impact, etc.

- Assign an effort score (1–5) across system complexity, variability, exceptions, etc.

- Plot them in the matrix.

What matters is not precision but relative positioning. You want to see which processes clearly fall in the “sweet spot” and which are resource drains

Real-World Application: A Banking Example

A regional bank faced this dilemma: should they automate loan disbursement checks or account closure requests first?

- Loan disbursement checks scored high on value (delays frustrated customers, and errors carried regulatory risk). But the effort was also high: multiple systems, inconsistent rules, and frequent policy changes.

- Account closure requests were low value (small volume) but very low effort (simple data entry).

The decision? Start with account closures to build confidence and free up capacity, but in parallel, design a roadmap for the loan disbursement automation. That sequencing was critical. Jumping straight into the high-value, high-effort project would have stalled momentum.

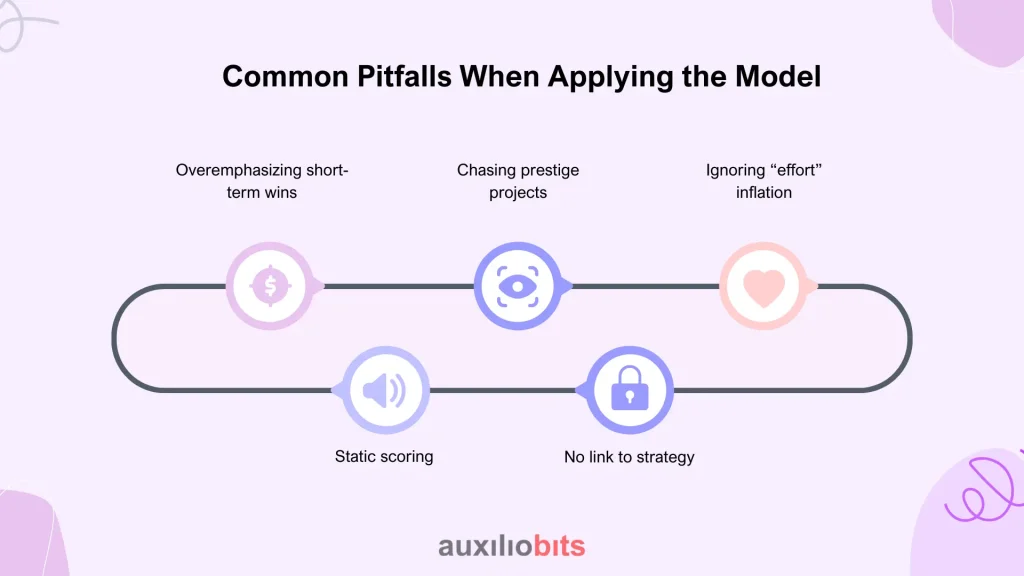

Common Pitfalls When Applying the Model

Even with a solid framework, organizations fall into traps:

- Overemphasizing short-term wins: Quick wins are great, but if you never graduate to strategic processes, automation stays a sideshow.

- Chasing prestige projects: Leaders often want flashy use cases—like AI chatbots—without considering effort or adoption.

- Ignoring “effort” inflation: Vendors may downplay complexity to close deals. Always ask for examples from similar environments.

- Static scoring: Value and effort shift as systems evolve. A process that looks hard today may become easier after a core ERP upgrade.

- No link to strategy: Automating payroll exceptions might score well on the grid, but if your company’s priority is faster order fulfillment, you’re misaligned.

Practical Tips for Making It Stick

- Don’t overpromise savings. Frame automation as capacity release, not immediate headcount cuts.

- Involve both business and IT in scoring—otherwise, you’ll miss half the picture.

- Pilot the scoring on a small set of processes first; refine the criteria before scaling.

- Reassess annually. Business priorities change; so should your automation pipeline.

- Document assumptions. If you rated “effort = low” because the system is “stable,” make that explicit—so when the system changes, you know why your rating breaks.

Why the Model Works

The value-to-effort model works because it forces explicit trade-offs. Instead of arguing endlessly about “what’s most important,” you put processes on the map and have a visual framework for discussion.

But it fails when leaders use it mechanically. I’ve seen processes ranked “3.8” on value and “2.7” on effort, and decisions stalled because nobody wanted to interpret the nuance. Remember: the framework is a guide, not a verdict. The conversation it sparks is more important than the score itself.

A Final Thought

Process selection is not glamorous. It doesn’t make vendor brochures. But it determines whether automation becomes a strategic lever or a forgotten experiment. The value-to-effort model won’t solve every debate, but it gives you a disciplined way to channel energy toward the right places.

And here’s the paradox: sometimes the “right” process to automate isn’t the most valuable or the easiest—it’s the one that builds trust. If automating a modest, low-effort workflow convinces skeptical stakeholders that automation works, it may unlock bigger opportunities down the road. Frameworks aside, that kind of judgment call is what separates successful automation leaders from the rest.