Key Takeaways

- Agent-first architecture transforms software from reactive code to proactive participants. Traditional API-driven systems execute commands; agentic systems interpret goals, reason contextually, and collaborate toward outcomes.

- The revolution is architectural, not algorithmic. While LLMs and AI models power reasoning, the real shift lies in how software is structured—around goals, context, and adaptive coordination instead of static workflows.

- Governance and transparency are the new scalability challenges. Enterprises must embed oversight, explainability, and policy constraints directly into agentic ecosystems to maintain trust and compliance.

- The competitive edge will come from meta-orchestration. Success won’t depend on having the smartest individual agent but on who builds the best coordination layer—the “meta-agent” that safely manages autonomy at scale.

- The next decade of enterprise software will prize resilience over efficiency. Systems that can negotiate, adapt, and self-correct will outperform those that simply automate faster—marking a fundamental shift in what defines digital maturity.

It’s tempting to treat “agent-first architecture” as another tech buzzword. After all, we’ve been through our fair share of architectural revolutions: client-server, service-oriented, microservices, event-driven, API-first—you name it. Each era promised flexibility, modularity, and intelligence. But this time, the shift isn’t about structure. It’s about behavior.

Agent-first architectures don’t just change how software is built—they redefine how it acts. The components of an agentic system aren’t passive executors of code. They reason, plan, and make trade-offs in real time. That’s an entirely different design philosophy—closer to an organizational model than a traditional software stack.

And that’s exactly why it matters.

Also read: The Role of Intent Recognition in Multi-Agent Orchestration

From APIs to Autonomous Participants

For the past decade, enterprise systems have revolved around APIs and workflows. Each component had a clear contract: input, process, and output. If something broke, you looked for a failed service or misconfigured endpoint. Predictable, mechanical, reliable.

Agent-first systems don’t behave that way. They replace those rigid handshakes with negotiations. One agent requests data from another, not with a static API call, but with an intent—“find me the best supplier given these constraints.” The receiving agent doesn’t just fetch from a database; it evaluates, contextualizes, and responds based on its understanding.

It’s not that APIs disappear—they just fade into the background, replaced by goal-oriented collaboration.

Consider a procurement system built on agents. Instead of predefined workflows—create purchase order → get approval → send to supplier—you have agents representing each function:

- A Budget Agent enforcing spending limits dynamically.

- A Compliance Agent vetting suppliers against updated policies.

- A Negotiation Agent that autonomously seeks better terms or bulk discounts.

These agents don’t just “run” a process—they cooperate toward an outcome. The old model was optimized for control. The new one optimizes for adaptability.

Why This Isn’t Just About AI

It’s easy to assume this shift is driven by AI advancements—and yes, large language models (LLMs) and reinforcement learning play critical roles. But the real transformation is architectural, not algorithmic.

Agent-first systems challenge how we think about software autonomy. Instead of building systems that need human orchestration, we design systems that orchestrate themselves.

A few principles define this shift:

- Goal orientation over task sequencing. Agents are driven by objectives, not linear scripts.

- Contextual awareness. Agents maintain state, history, and situational understanding.

- Dynamic coordination. Workflows are emergent, not pre-coded.

- Continuous learning. Performance improves from feedback and outcomes, not just retraining cycles.

You could argue that this isn’t new. Multi-agent systems have been around for decades—in robotics, logistics, and even financial trading. What’s different now is computational maturity: scalable LLMs, vector databases, fast message brokers, and cloud-native observability layers. Suddenly, the economics and infrastructure align with the ambition.

The Strategic Relevance for Enterprises

The question executives are quietly asking isn’t can we build agentic systems—it’s should we?

Because autonomy comes with trade-offs. The same flexibility that lets agents reason independently also introduces unpredictability. If one agent decides to delay an approval for “risk evaluation,” how do you ensure it aligns with company policy?

This tension between autonomy and governance is shaping what we’d call the next-gen enterprise operating model:

- Agents handle micro-decisions that require speed or adaptability.

- Humans define macro-policies that constrain the decision space.

- Architects design meta-governance—rules for how agents negotiate, prioritize, and escalate.

In practice, this means CFOs won’t sign off on every transaction, but their digital finance agent will operate under risk thresholds they define. HR won’t manually review resumes, but its screening agent will interpret job descriptions using company-specific ethics and diversity guidelines.

That’s why CIOs and CTOs need to think beyond implementation. They’re not deploying software—they’re designing behavior ecosystems.

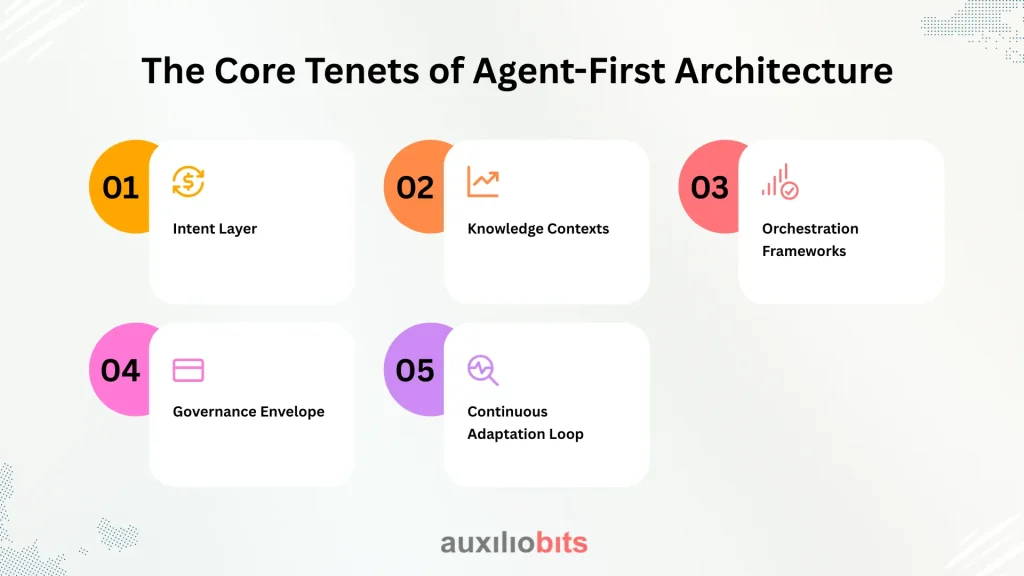

The Core Tenets of Agent-First Architecture

Underneath the hype, a few architectural patterns are becoming standard. They aren’t all formalized yet (give it another two years), but we’re seeing consistent motifs emerge across industry pilots:

1. Intent Layer

Instead of direct function calls, agents communicate via intents—structured goal representations. “Approve vendor within budget” replaces “POST /approveVendor.” This makes reasoning and negotiation possible.

2. Knowledge Contexts

Each agent has access to a context store—structured and unstructured memory drawn from APIs, documents, and event logs. This is how agents maintain continuity and avoid stateless redundancy.

3. Orchestration Frameworks

Traditional workflow engines give way to agent coordinators—meta-agents that monitor, mediate, and delegate goals dynamically. These frameworks often integrate message queues, embeddings, and reinforcement signals.

4. Governance Envelope

Policies, audit trails, and explainability layers become non-negotiable. Without them, you don’t have enterprise software—you have chaos. Governance layers track agent decisions, constrain autonomy, and provide rollback mechanisms

5. Continuous Adaptation Loop

Agents learn from results—successes, failures, and delays—and adjust strategies. This often combines reinforcement signals with vector-based similarity searches to identify past analogs.

None of this is trivial. Each element redefines long-standing assumptions about reliability, observability, and debugging. When a workflow fails, do you log it as a system error—or as a “misjudgment” by an autonomous entity?

The Industry Prototypes Are Already Here

It’s not a theory anymore. Some industries are already experimenting—quietly, but seriously.

1. Financial Services:

Agentic trade execution platforms already exist, where autonomous trading agents negotiate across portfolios, optimizing for liquidity and compliance simultaneously. These systems don’t just automate trades; they negotiate intent alignment between market and regulatory objectives.

2. Manufacturing:

In smart factories, agentic control systems manage material flows dynamically. A supply agent detects late shipments, negotiates substitute orders, and coordinates with production planning—all without human intervention.

3. Healthcare:

Clinical trial management is becoming agent-driven. Agents track enrollment, compliance, and data integrity—coordinating between CROs, hospitals, and patient systems. They don’t “replace” administrators; they relieve them of combinatorial complexity.

These implementations reveal something subtle: agent-first design doesn’t replace enterprise software—it reforms it from within.

ERP systems still exist. CRMs still exist. But instead of users adapting to their rigidity, agents adapt those systems’ behaviors to the organization’s intent.

What Breaks in the Transition

Every architectural leap comes with failure patterns. Agent-first is no different. The problems aren’t just technical—they’re conceptual.

1. Misaligned Objectives

Agents that optimize locally can create global inefficiencies. For example, a sales agent maximizing close rates might overcommit resources that a fulfillment agent can’t handle. Coordination mechanisms must evolve from static dependencies to shared goal models.

2. Trust and Transparency

Explainability isn’t optional. If an agent denies a purchase request or flags a transaction, it must justify why—ideally in human-readable terms. The absence of interpretable reasoning undermines adoption faster than any technical bug.

3. Data Fragmentation

Agents thrive on shared context. Without unified data layers or access controls, they operate in silos—leading to contradictory actions or duplicated efforts. Ironically, autonomy without interoperability creates more chaos, not less.

4. Latency of Oversight

By the time a compliance officer reviews an agent’s action, the impact might already be live in production. Governance needs to move from post-factum review to real-time policy embedding.

5. Cognitive Load on Humans

Ironically, agentic systems can overwhelm human operators with too much “autonomy noise.” Instead of micromanaging tasks, they start micromanaging agents. The solution? Visual governance dashboards that summarize intent flows and negotiation outcomes.

Agent-first architecture isn’t fragile because of technology—it’s fragile because it changes how humans think about systems.

The Platform Race Has Begun

Every major cloud and enterprise vendor is quietly pivoting toward agentic capabilities.

- Microsoft is embedding Copilot agents deep into enterprise stacks—from Outlook to Dynamics 365. The next logical step: connecting them across domains.

- Salesforce has introduced Einstein 1, a meta-layer that acts as an agentic integration fabric.

- ServiceNow is rebranding workflows as “AI-driven actions,” a precursor to full autonomy.

- SAP and Oracle are experimenting with internal agents that bridge data silos, not just automate transactions.

The real competition, however, isn’t about models or APIs—it’s about governed orchestration. Whoever builds the best meta-agent layer—the one that coordinates others safely and scalably—wins the enterprise adoption race.

The Human Paradox

Agent-first architectures don’t eliminate humans; they reposition them. Decision-making becomes meta-decision-making: setting goals, designing constraints, and defining “what good looks like.”

This might sound abstract, but it mirrors management theory. In organizations, leaders delegate authority but retain accountability. Software will soon operate on the same principle.

Paradoxically, the more we automate, the more important human judgment becomes. Not in execution, but in ethics, boundary-setting, and sense-making. You’ll need architects who understand cognitive systems, not just Kubernetes clusters. You’ll need designers who think in behavior models, not just user interfaces.

And, perhaps most importantly, you’ll need trust. Not blind faith in algorithms, but trust in how autonomy is structured.

The Decade Ahead: What Will Define Success

Over the next ten years, we’ll see two parallel realities emerge.

In one, companies deploy “AI assistants” inside existing workflows—a layer of convenience. They’ll save time, automate documentation, and even make recommendations. But they’ll still be bound by legacy logic.

In the other, companies will architect for agencies—building systems where agents aren’t add-ons but core participants. These systems will:

- Continuously coordinate toward outcomes, not checklists.

- Adapt to context drift without retraining.

- Collaborate with other agents, human or digital, via shared protocols.

- Explain their decisions as fluently as they make them.

The first group will gain efficiency. The second will gain resilience.

And that’s the real prize. In a world where conditions shift faster than release cycles, resilience—not intelligence—will define competitive advantage.

A Final Thought

If the past few decades were about making systems programmable, the next will be about making them negotiable. Software will no longer wait for explicit instructions; it will interpret, debate, and decide within defined bounds.

Agent-first architectures are not a passing trend. They’re the beginning of a long, complex redefinition of what “enterprise software” even means. Ten years from now, we might look back and realize that this wasn’t an AI revolution at all—it was an architectural awakening.

Because once software starts thinking in goals instead of functions, the game changes—for good.