Key Takeaways

- Manufacturing Automation CoEs must evolve from task-focused delivery units into strategic operating models that govern, guide, and steward autonomous digital labor across the enterprise.

- Agentic automation shifts value creation from speed and volume of bots to the quality of decisions, judgment integrity, and controlled autonomy embedded within systems.

- Skills like systems thinking, domain expertise, and data literacy are more critical in the agentic era than deep specialization in any single automation platform.

- Governance for agentic systems should concentrate on setting limits for autonomy, determining outcome standards, and ongoing monitoring of behaviour instead of relying on fixed approvals and yearly audits.

- Platform-agnostic CoEs are better positioned to handle manufacturing complexity, legacy environments, and evolving agent architectures without forcing solutions to fit tool limitations.

For years, manufacturing firms have been building Automation Centers of Excellence (CoEs) with a fairly predictable playbook: a small RPA team, a pipeline of use cases, a governance checklist, and a value tracker that looks excellent in quarterly reviews. It worked—until it didn’t.

The agentic era changes the assumptions underneath that model. When automation moves from scripted tasks to autonomous, decision-capable systems, the CoE stops being a “bot factory” and starts resembling a socio-technical operating model. The old constructs creak under the weight of new expectations: self-directed agents, cross-functional orchestration, real-time learning, and a much blurrier line between IT and business.

Some organizations are already feeling this. An automotive supplier had a mature RPA CoE—over 300 bots, respectable ROI, and decent stakeholder satisfaction. Then they introduced AI-driven scheduling agents. Within six months, they hit more governance debates than they had in the previous three years. Who owns the agent’s decisions? How do you audit something that learns? Why did procurement get value while quality assurance didn’t? The CoE wasn’t broken; it was just built for a different era.

Building a Manufacturing Automation CoE for the agentic age requires rethinking skills, roles, governance, and—quietly but critically—philosophy.

Also read: How Manufacturing Leaders Are Building Autonomous Operations

From Bot Factory to Autonomy Engine

Traditional CoEs were optimized for:

- Repeatability

- Determinism

- Clear input-output logic

- Stable processes

Agentic systems thrive in messier conditions:

- Ambiguous inputs

- Multi-step reasoning

- Cross-system negotiation

- Evolving rules

In a plant environment, that difference matters. A bot that posts GRNs into ERP is easy to reason about. An agent that monitors supplier performance, predicts shortages, triggers alternate sourcing, and negotiates delivery windows? That’s not a “task.” That’s a miniature operating unit.

The implication is uncomfortable for some leaders: the CoE can’t just be a delivery arm anymore. It becomes a steward of digital labor.

And stewardship requires more than developers and dashboards.

Skills: What Actually Matters

Most CoEs still over-index on platform skills. “We need more UiPath developers.” “We need Power Automate certifications.” Platform competence matters, but in the agentic context, it’s table stakes.

The differentiating skills look more like this:

1. Systems Thinking

Agents don’t operate in isolation. They influence upstream planning, downstream execution, and exception handling in ways that ripple through the enterprise.

People who understand:

- How MRP decisions cascade into shop floor volatility

- Why a change in credit policy affects order release

- Where manual workarounds hide operational truth

…are far more valuable than someone who only knows how to chain actions together.

2. Process + Domain Hybrids

The best automation architects in manufacturing are rarely “pure technologists.” They’re ex-planners, quality engineers, or finance analysts who learned automation—not the other way around.

Useful profiles include:

- Production planners who can model constraints and variability

- Supply chain analysts who understand demand distortion

- Finance professionals who know where revenue leakage hides

- QA leaders familiar with regulatory nuance

Agentic systems amplify judgment. If judgment is flawed, autonomy just accelerates the wrong outcomes.

3. Data Literacy

You don’t need an army of PhDs. You do need people who can:

- Question data sources

- Understand latency, bias, and gaps

- Interpret confidence levels

- Recognize when an agent is hallucinating operational truth

In one food processing firm, an inventory optimization agent kept recommending “zero safety stock” for slow-moving SKUs. Mathematically sound. Operationally reckless. The issue wasn’t the model—it was the absence of someone who understood demand volatility in seasonal markets.

4. Ethical and Risk Awareness

It sounds lofty, but it shows up in mundane ways:

- Should an agent auto-reject a supplier invoice?

- Can it deprioritize certain customers based on margin?

- Is it allowed to bypass human approval in compliance workflows?

Without people trained to think in risk, fairness, and accountability, governance becomes performative.

Roles: The Org Chart Needs a Rewrite

Most CoEs are still structured around delivery mechanics:

- Developers

- Solution architects

- QA

- Support

- Program manager

The agentic shift introduces roles that feel unfamiliar, sometimes awkwardly so.

1. Agent Product Owners

Not business analysts. Not IT owners. Something in between.

They:

- Define the “behavioral contract” of agents

- Decide what autonomy is allowed

- Prioritize learning objectives

- Own business outcomes, not just deployment

2. Orchestration Architects

Agentic environments are rarely single-agent systems. They’re ecosystems.

This role focuses on:

- Multi-agent coordination

- Conflict resolution logic

- Escalation pathways

- Human-in-the-loop integration

Think less “build me a workflow” and more “design me a digital organization.”

3. Digital Workforce Ops

Someone has to run the agents like employees:

- Performance monitoring

- Incident management

- Capacity planning

- Continuous improvement

4. Governance & Risk Stewards

Not auditors. Not compliance police.

They:

- Define acceptable autonomy boundaries

- Maintain auditability

- Manage regulatory exposure

- Review emergent behaviors

The position’s effectiveness is compromised if it reports excessively to IT, yet it becomes a hindrance if placed too deeply within compliance. Maintaining the right equilibrium is crucial.

Governance: Where Most CoEs Quietly Fail

Governance in traditional automation was about control: approvals, standards, templates, checklists. In agentic systems, control gives way to oversight and intent management.

A few principles that hold up in real environments:

1. Shift from “Approval Gates” to “Autonomy Levels”

Not every process deserves the same freedom.

Define tiers:

- Level 0: Advisory only (agent recommends, human decides)

- Level 1: Assisted execution (agent acts, human reviews)

- Level 2: Conditional autonomy (agent acts within constraints)

- Level 3: Full autonomy with audit

Most manufacturers discover that only a small fraction of processes should ever reach

Level 3. That’s fine. The mistake is pretending everything should.

2. Outcome-Based Governance

Stop governing how something is built. Govern what it’s allowed to do.

Examples:

- Maximum financial exposure per autonomous decision

- Customer impact thresholds

- Compliance-critical checkpoints

- Safety-related exclusions

3. Continuous Review, Not Annual Audits

Agents learn. Environments change. Static governance ages poorly.

Effective CoEs run:

- Monthly behavior reviews

- Drift analysis

- Exception pattern analysis

- Stakeholder feedback loops

Yes, it sounds heavy. In practice, it’s lighter than dealing with a public failure.

Platform-Agnostic by Design

“Platform-agnostic” gets thrown around casually. Most CoEs say it while being deeply locked into one vendor.

In manufacturing, platform agnosticism is not ideological—it’s pragmatic.

Plants run:

- Legacy MES

- Multiple ERPs

- Homegrown planning tools

- Vendor portals

- Excel (still, always Excel)

If your CoE is married to one automation stack, you’ll:

- Overfit solutions to platform capabilities

- Force unnatural architectures

- Miss opportunities outside the tool’s comfort zone

A pragmatic approach looks like:

- Choosing the right tool per problem (RPA, iPaaS, agents, scripts, APIs)

- Designing loosely coupled architectures

- Avoiding proprietary lock-in where possible

- Building abstraction layers around critical logic

It’s messier than a single-platform strategy. It’s also more resilient.

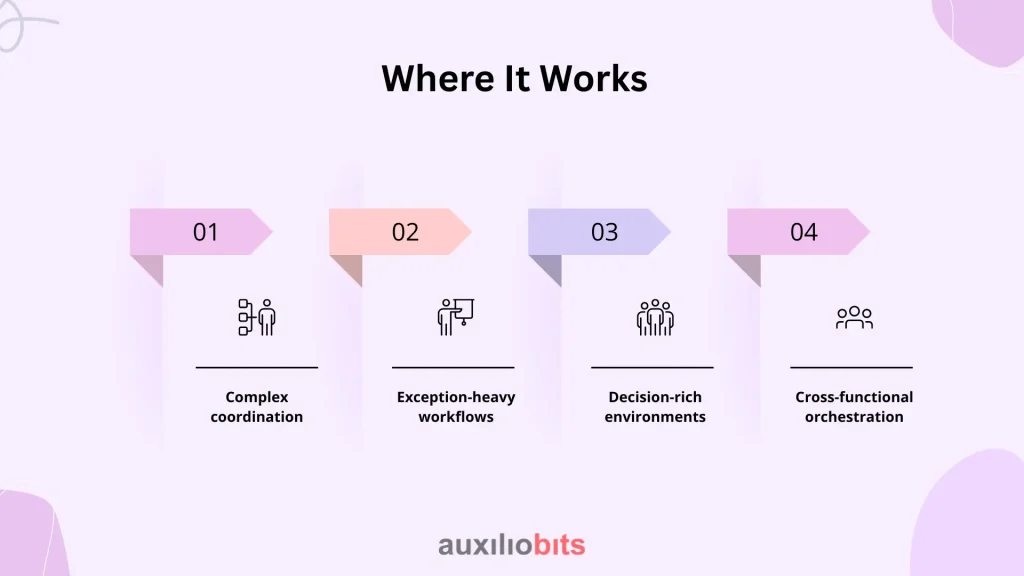

Where It Works… and Where It Breaks

Agentic CoEs shine in:

- Complex coordination (order-to-cash, procure-to-pay, planning)

- Exception-heavy workflows

- Decision-rich environments

- Cross-functional orchestration

They struggle in:

- Highly unstable processes

- Politically contested workflows

- Poor data environments

- Cultures allergic to transparency

Hard Realities

A few observations that don’t always make it into slide decks:

- Not everything should be autonomous. Some decisions benefit from friction.

- Agentic systems expose bad process design. Loudly.

- Value realization shifts from speed to quality of judgment.

- CoEs need political capital, not just technical skill.

- If your CoE reports only to IT, you’re already constrained.

And perhaps the most inconvenient: building this well is slower than spinning up bots—but the payoff compounds.

What a Mature Agentic CoE Feels Like

Walk into a mature Manufacturing Automation CoE in the agentic era and you’ll notice a few things:

- Conversations are about outcomes, not features

- Plant managers attend design reviews

- Finance trusts the numbers

- Exceptions are treated as learning, not failure

- Platforms are tools, not identities

- Humans and agents coexist without paranoia

It doesn’t look flashy. It looks operationally calm. Which, in manufacturing, is often the highest compliment.

The agentic era doesn’t kill the CoE. It forces it to grow up.

And honestly, some of them needed that.