Key Takeaways

- Product categorization is not a classification problem—it’s a decision problem. Treating categorization as a single prediction ignores ambiguity, business rules, and evolving taxonomies. Real-world catalogs demand systems that can reason, hesitate, and escalate when needed.

- Most LLM failures stem from structure, not intelligence. Overconfidence, fragility, and lack of learning aren’t signs of weak models. They’re symptoms of linear pipelines that force every input into a one-shot decision without memory or context.

- LangGraph’s real value lies in controlled reasoning, not orchestration. The ability to branch, pause, revisit signals, and route edge cases makes LangGraph suited for high-stakes operational decisions—especially where “no decision yet” is better than a wrong one.

- Human feedback only matters if it changes future behavior. Logging corrections isn’t enough. Systems improve when feedback updates routing logic, rule exceptions, and trust signals—not just training data.

- The goal isn’t full automation; it’s predictable behavior under uncertainty. High-performing categorization systems don’t aim to eliminate humans immediately. They aim to automate the obvious, surface the ambiguous, and steadily reduce manual effort through better decision design.

Product categorization is one of those problems that sounds boring until it breaks. When it breaks, conversion drops, search relevance tanks, and suddenly the merchandising team is in meetings twice a day arguing over whether “wireless earbuds with ANC” belong under Audio Accessories, Wearables, or Consumer Electronics > Headphones. Multiply that by a catalog of 500,000 SKUs coming from dozens of vendors, each with their own naming quirks, and you get a sense of why this problem refuses to stay “solved”.

Most e-commerce platforms still rely on a mix of rules, keyword matching, and periodic human audits. That approach works—until it doesn’t. The moment catalogs become dynamic, multilingual, or vendor-driven, static logic collapses. This is where autonomous categorization becomes intriguing, and where LangGraph, specifically, offers something that traditional LLM pipelines do not. We are not claiming LangGraph is magic. It isn’t. But it does force you to consider categorization as a decision system rather than a single inference call. That shift matters more than the tool itself.

Why categorization is harder than people admit

Most teams underestimate the problem because they look at it as a classification task. Train a model, map labels, and deploy. In practice, categorization behaves more like a negotiation between signals.

A real product listing doesn’t come neatly packaged:

- Titles are marketing-driven (“Pro Max Ultra Edition”).

- Descriptions are copy-pasted across SKUs with slight variations.

- Attributes are incomplete or vendor-defined (“Type: Regular” — regular what?).

- Images contradict text more often than anyone likes to admit.

And then there’s taxonomy drift. Categories change. Business priorities shift. Seasonal collections get added and removed. The model that performed well six months ago quietly starts making wrong decisions, but not wrong enough to trigger alerts.

This is why simple prompt-based LLM categorization feels impressive in demos and disappointing in production.

Also read: LangChain vs LangGraph: choosing the right orchestration framework for agentic automation

Where LLM-based categorization usually fails

Before getting into LangGraph or any orchestration pattern, it’s worth being honest about where most LLM-based categorization systems break down in real production environments. The issues aren’t subtle. They show up as noisy categories, rising manual audits, and quiet erosion of search and discovery quality.

What’s important is that these failures are not model-quality problems. Teams often try to solve them by refining prompts or upgrading to a larger model, which may help temporarily. But the root cause is structural. Single-pass LLM categorization treats a complex decision as a one-shot prediction, without context, memory, or recourse.

Here are the most common failure modes seen in the field.

| Failure Mode | What is looks like in practice | Why it breaks at scale |

| Overconfidence | The model assigns a specific category with high certainty even when titles, attributes, or images are vague or contradictory. | LLMs are designed to be decisive. Without an explicit mechanism to express uncertainty, the system guesses—and those guesses propagate across large catalogs. |

| Single-shot fragility | A minor prompt change or taxonomy update causes misclassification across thousands of unrelated SKUs. | When categorization happens in a single inference call, there’s no separation between extraction, reasoning, and decision. One change affects everything. |

| No memory of policy | Category definitions and exclusion rules live in PDFs, emails, or Confluence pages, disconnected from runtime logic. | The model has no persistent understanding of business constraints or historical decisions, so every classification starts from scratch. |

| No escalation logic | Ambiguous products, bundles, or hybrid SKUs are treated the same way as straightforward items. | Without confidence thresholds or branching paths, the system cannot pause, re-evaluate, or route edge cases for deeper analysis or review. |

| No feedback incorporation | Human corrections enhance individual products but don’t reduce future errors. | Feedback is recorded but not operationalized. The system doesn’t adapt its reasoning or routing based on past mistakes. |

Most teams respond to these problems by layering on more prompts, longer instructions, or larger models. That approach can mask the symptoms for a while, but it doesn’t change the underlying behavior of the system. To do that, the categorization pipeline itself needs to evolve—from a single decision into a structured reasoning flow.

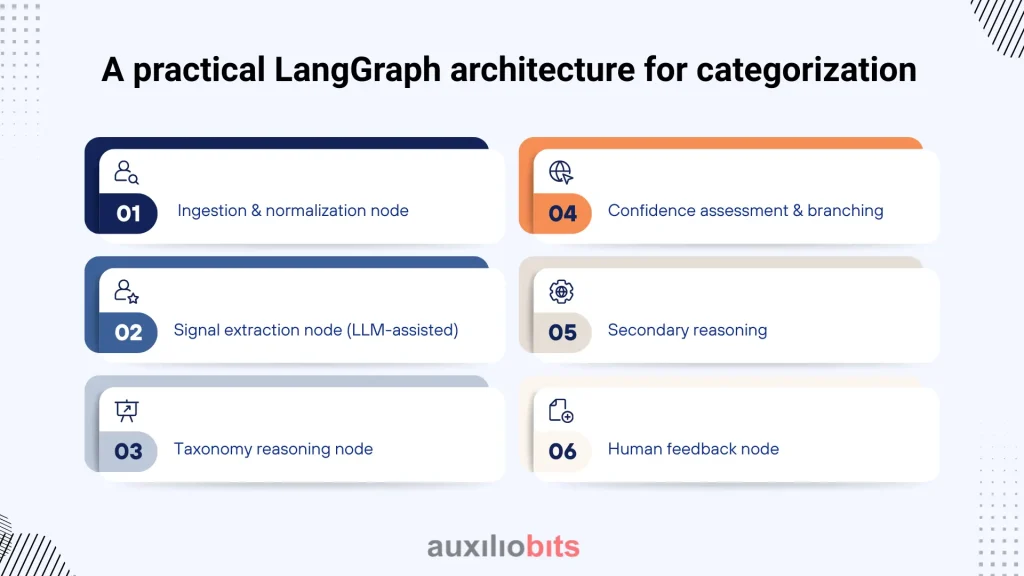

A practical LangGraph architecture for categorization

Let’s walk through a real-world design, not an academic one.

1. Ingestion & normalization node

This node doesn’t use an LLM at all. It cleans and structures input:

- Normalize titles (remove promotional fluff where possible).

- Parse attributes into a consistent schema.

- Detect language and translate if required.

- Attach vendor metadata (trusted vs long-tail sellers).

This matters because garbage-in still applies, no matter how large your model is.

2. Signal extraction node (LLM-assisted)

Here, an LLM extracts signals, not categories.

Think in terms of:

- Primary product function

- Physical vs digital

- Consumable vs durable

- Brand relevance

- Regulatory sensitivity (medical, food, cosmetics)

This node might output something like:

Primary use: personal audio

Form factor: in-ear

Power: rechargeable

Smart features: noise cancellation, touch control

Notice there’s no category yet. That’s deliberate.

3. Taxonomy reasoning node

Now the system reasons against your actual taxonomy, not a generic one.

This node:

- Loads category definitions (often as structured text, not raw PDFs).

- Applies inclusion/exclusion rules.

- Flags conflicts (e.g., “wearable” vs “audio accessory”).

This is where LangGraph shines because the state includes:

- Extracted signals

- Business rules

- Historical categorization patterns

If ambiguity crosses a threshold, the graph branches.

4. Confidence assessment & branching

This is one of the most underrated steps.

Instead of forcing a decision, the system evaluates:

- Signal consistency

- Rule alignment

- Similarity to past SKUs

Outcomes may include:

- High confidence → auto-assign

- Medium confidence → secondary reasoning pass

- Low confidence → human-in-the-loop

This branching logic is painful to implement cleanly in linear chains. In LangGraph, it’s the point.

5. Secondary reasoning

For borderline cases, the system might:

- Compare against top-N similar products

- Analyze images (if available)

- Re-check vendor history (are they usually misclassified?)

This is slower, more expensive, and intentionally limited to edge cases.

That trade-off—speed vs certainty—is explicit in the graph, not hidden in prompt hacks.

6. Human feedback node

When humans intervene, their corrections are not just logged.

They update:

- Rule exceptions

- Vendor reliability scores

- Future routing logic

Over time, the graph evolves. Not autonomously in a scary way, but operationally smarter.

Why this works better than single-pass LLMs

The benefit isn’t accuracy alone. It’s behavior under uncertainty.

LangGraph-based systems:

- Hesitate when they should

- Escalate instead of guessing

- Learn structurally, not just statistically

That last point matters. Many teams try to fine-tune models on corrected labels. That helps, but it doesn’t encode why a decision was wrong.

Graphs do.

LangGraph vs traditional workflow engines

People often ask whether this could be done with BPM tools or rule engines.

Technically, yes. Practically, not quite.

Traditional engines:

- Struggle with probabilistic reasoning

- Treat LLMs as opaque services

- Don’t manage state-rich AI decisions well

LangGraph is opinionated around LLM-centric workflows. That’s both its strength and its limitation.

Autonomous categorization isn’t about replacing merchandisers. It’s about freeing them from repetitive arbitration so they can focus on taxonomy design, vendor strategy, and experience quality.

LangGraph doesn’t solve categorization. It gives you a framework to build systems that behave like experienced operators, not just classifiers.

And once you see categorization as a decision graph instead of a prompt, it’s hard to go back.