Key Takeaways

- Agentic design thinking reframes design from building tools to designing decision authority. The core shift is no longer about interfaces or workflows, but about who—or what—is allowed to observe, decide, act, and escalate within enterprise systems.

- Autonomy without boundaries creates risk, not speed. Successful agentic systems operate within explicitly designed constraints, escalation paths, and confidence thresholds rather than open-ended independence.

- Human value moves upstream in agentic organizations. As agents handle execution and continuous monitoring, human contribution shifts toward goal-setting, judgement, ethical oversight, and exception handling.

- Decision journeys matter more than user journeys in automated environments. Smooth user experiences can hide fragile decision logic; mapping decision ownership and authority exposes where agentic systems truly succeed or fail.

- Learning must be designed as a governed capability, not an emergent behavior. Enterprises that separate operational learning from strategic control avoid both system drift and stagnation while retaining accountability.

Most leadership teams already understand design thinking. Or at least, they believe they do. Empathize with users, define the problem, ideate, prototype, test—repeat. It’s been on executive offsites, innovation decks, and consulting frameworks for over a decade. And yet, something feels increasingly misaligned.

Design thinking assumes humans are the primary actors: gathering insights, making decisions, and iterating solutions. That assumption quietly breaks down when AI systems stop being tools and start becoming participants. They are no longer mere assistants in the traditional sense. This is where agentic design thinking enters—not as a rebrand, but as a necessary evolution. Because when AI systems can observe, decide, act, and learn across workflows, the design question shifts from “What should we build?” to “Who is allowed to act, decide, and adapt—and under what constraints?”

Also read: Combining Agentic AI with iPaaS Tools for Scalable Integration

Why Traditional Design Thinking Starts to Fray

Classic design thinking works best in environments where:

- Humans experience the pain directly

- Problems are bounded in time and scope

- Decision loops are relatively slow

Now consider a modern enterprise process—say, credit risk monitoring or supplier onboarding. Continuous data streams are present. Decisions are probabilistic. Actions cascade across systems in seconds. No human “user” experiences the whole process end-to-end anymore.

Design thinking workshops still happen. Sticky notes still get filled. Personas still get named. But the actual work is happening elsewhere—inside event-driven systems, model-driven decisions, and automated escalations.

The mismatch shows up in subtle ways:

- Solutions feel elegant but brittle

- Edge cases dominate operational reality

- Humans approve decisions they didn’t meaningfully make

And when something breaks, leadership asks a familiar question: Why didn’t anyone catch the error earlier? Often, the answer is uncomfortable: because no single human was actually “doing” the work anymore.

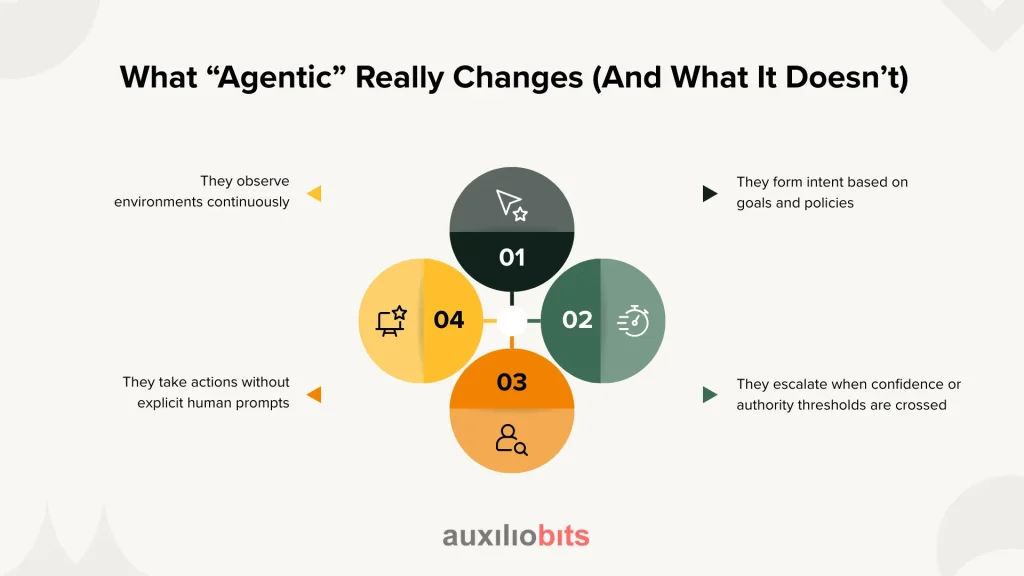

What “Agentic” Really Changes (And What It Doesn’t)

There’s a tendency to treat “agentic” as synonymous with autonomy. That’s sloppy thinking.

Agentic systems aren’t defined by how independent they are. They’re defined by how they exercise constrained agency:

- They observe environments continuously

- They form intent based on goals and policies

- They take actions without explicit human prompts

- They escalate when confidence or authority thresholds are crossed

Design thinking in this context can’t stop at empathy maps and journeys. It has to answer harder questions:

- Who sets goals vs. who optimizes toward them?

- Where does judgment live when trade-offs are messy?

- How does learning occur without drifting into risk?

Agentic design thinking doesn’t eliminate human-centeredness. It redistributes it. Humans move from being primary actors to being:

- Goal-setters

- Boundary designers

- Ethical arbiters

- Exception handlers

That redistribution is where most organizations stumble—not technically, but culturally.

Designing for Delegation, Not Control

One of the most significant mental shifts leaders struggle with is designing for delegation rather than for control.

Traditional systems are built around approvals:

- If X happens, route it to the manager

- If the threshold is exceeded, please request a sign-off.

- If unsure, wait

Agentic systems don’t wait well. Nor should they.

Designing for delegation means explicitly deciding:

- What is an agent trusted to decide alone?

- What decisions require consultation

- What decisions must never be automated?

This sounds obvious. It isn’t.

Agentic Design Thinking Is About Tension

Design thinking often aims for harmony: alignment between users, systems, and outcomes. Agentic environments are messier. Tension is unavoidable.

Effective agentic design acknowledges competing forces:

- Speed vs. explicability

- Optimization vs. fairness

- Autonomy vs. accountability

Ignoring these tensions doesn’t remove them—it just pushes them into failure modes.

Consider automated credit decisions. Faster approvals reduce friction and increase conversion. But they also amplify bias if feedback loops aren’t monitored. Designing an agentic system here isn’t about picking a side. It’s about structuring who intervenes when trade-offs surface.

Some teams handle this well by:

- Allowing agents to decide within a confidence band

- Routing borderline cases to human reviewers

- Periodically re-evaluating thresholds based on outcomes

Others pretend the tension doesn’t exist—until regulators, customers, or auditors remind them.

From User Journeys to Decision Journeys

One of the more practical shifts in agentic design thinking is moving from user journeys to decision journeys.

User journeys ask:

- What does the user experience?

- Where do they feel friction?

- How do we reduce steps?

Decision journeys ask different questions:

- What decisions are made at each stage?

- Who (or what) makes them?

- What information is available at the time?

- What happens when information is incomplete?

In procurement automation, for example, the user journey might look smooth. Forms auto-fill. Approvals move faster. But the decision journey might be fragile:

- Supplier risk is assessed once, not continuously.

- Exceptions handled inconsistently

- Learning loops are missing.

Agentic design thinking forces teams to map decision ownership explicitly. It’s not just about flows but also about authority.

Designing for Learning Without Letting Systems Drift

Here’s where many leaders get nervous—and not without reason. If agents learn, they change behavior. If behavior changes, predictability decreases. If predictability decreases, risk increases. Or so the thinking goes.

The reality is more nuanced. Learning doesn’t have to mean unchecked adaptation. Agentic design thinking distinguishes between:

- Operational learning (tuning thresholds, prioritization)

- Strategic learning (changing goals or policies)

Most enterprise agents should only do the former. The latter remains firmly human-owned.

Practical design patterns that work:

- Freezing certain decision rules while allowing others to adapt

- Logging human overrides as training signals

- Learning outcomes should be reviewed in governance forums rather than on an ad-hoc basis.

Agentic design thinking isn’t about making organizations more automated. It’s about making them more intentional.

When systems can act, the absence of design becomes visible. Culture leaks into code. Assumptions turn into policies. Unspoken norms become operational risks.

Business leaders don’t need to become AI experts. They need to become designers of agency—deciding where autonomy belongs, where it doesn’t, and how learning happens without losing control.

That work is less glamorous than model selection or platform demos. But it’s where the real leverage sits.