Key Takeaways

- Agent as a Service is defined less by autonomy and more by accountability, ownership, and risk allocation between vendor and enterprise.

- Most AaaS business models break down under real operational volatility, revealing pricing and responsibility gaps that demos rarely expose.

- Hybrid “managed autonomy” models are emerging not as compromises, but as pragmatic responses to enterprise risk tolerance.

- AaaS delivers the most value where decision loops are frequent, bounded, and time-sensitive—not where judgment dominates.

- Market readiness for AaaS is uneven, and success depends more on disciplined scope and governance than on agent sophistication.

If you’ve spent any time around enterprise AI discussions over the last year, you’ve probably heard the phrase “Agent as a Service” dropped with casual confidence. Sometimes it’s said with the same tone people once used for SaaS—inevitable, obvious, already here. Other times it’s framed as the logical next step after chatbots and copilots. Both framings are partly right and partly misleading.

Agent as a Service (AaaS) is not just “SaaS with AI agents”. It represents a distinct commercial and operational offering. It reshapes how software is delivered, how value is priced, how risk is shared, and—quietly—how accountability is assigned when autonomous systems make decisions on behalf of a business. This final phase presents a significant challenge and is often overlooked.

Also read: Agents as Frontline Advisors in Retail Loyalty Programs

What “Agent as a Service” Means

At its core, AaaS is the delivery of autonomous or semi-autonomous software agents as a managed, ongoing service. These agents don’t just respond to prompts. They observe systems, make decisions within constraints, trigger actions, and adapt over time.

That sounds straightforward until you realize how broad the definition has become.

Some vendors use “AaaS” to describe:

- Hosted AI agents that execute predefined workflows (often glorified RPA with LLM wrappers)

- Decision-support agents that recommend actions but don’t execute them

- Fully autonomous agents that negotiate prices, reroute logistics, approve exceptions, or rebalance portfolios

Those are not the same product category. Treating them as interchangeable is one reason buyers end up disappointed after pilots.

A useful way to think about AaaS is not what the agent does, but where responsibility sits.

Does the service provider:

- Own uptime, performance, and accuracy?

- Tune models and decision policies continuously?

- Absorb some operational risk when agents misfire?

If the answer is no, you’re probably looking at software sold with a services wrapper—not AaaS in any meaningful sense.

Why AaaS Is Emerging Now

There’s a tendency to credit foundation models for everything happening in agent-based systems. They matter, obviously. But models alone didn’t unlock AaaS. Three quieter shifts did.

First, enterprises finally standardized enough of their digital exhaust—APIs, event streams, logs—that agents have something consistent to observe and act upon. Ten years ago, automation failed not because logic was complex, but because every system was brittle and bespoke.

Second, cloud economics normalized managed services as the default procurement pattern. Paying for outcomes, usage, or capacity is no longer exotic. Boards understand it. Procurement teams tolerate it. Legal teams still complain, but they complain about everything.

Third—and this one doesn’t get enough airtime—business teams are exhausted. Chronic labor shortages, operational volatility, and shrinking margins have made “assistive tools” feel inadequate. Systems that eliminate work, rather than merely improving it, are in high demand.

That appetite is what AaaS vendors are responding to. Whether they can meet it is another matter.

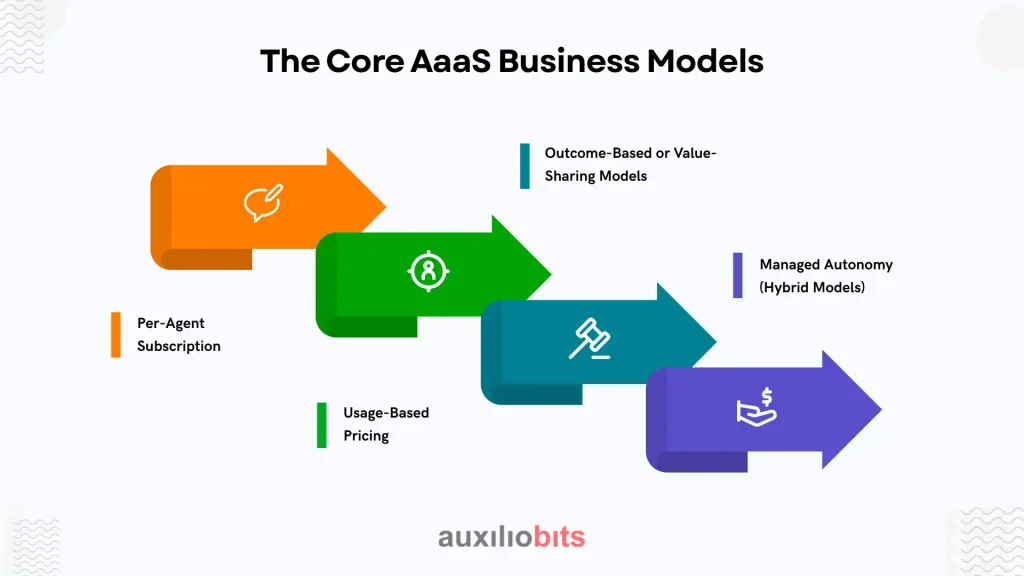

The Core AaaS Business Models

There is no single dominant commercial model for AaaS yet. What exists instead is a set of experiments, each with trade-offs that show up six months after go-live.

1. Per-Agent Subscription

This is the most familiar structure. You pay a monthly or annual fee per deployed agent.

It works well when:

- Agents are relatively static in scope

- Workloads are predictable

- The buyer wants budget clarity

It breaks down when:

- Agents scale actions non-linearly (one agent triggers hundreds of downstream events)

- Business value is tied to outcomes, not headcount replacement

- Clients start asking, “Why am I paying the same when volume tripled?”

There’s also an awkward question lurking here: what is an agent? Is an orchestrator agent plus five task agents one unit or six? Vendors and buyers often disagree.

2. Usage-Based Pricing

Some AaaS offerings price by:

- Number of actions executed

- Decisions made

- Transactions processed

- Tokens consumed

This aligns cost with activity, which CFOs like in theory. In practice, it introduces anxiety.

Imagine a pricing agent during market volatility. Usage spikes precisely when businesses are already under stress. The invoice lands at the worst possible moment. Suddenly, autonomy feels expensive.

Usage-based models demand extremely transparent metering and forecasting. Few vendors are mature there yet.

3. Outcome-Based or Value-Sharing Models

This is the model that is frequently discussed at conferences but often avoided in contracts.

Examples include:

- Percentage of cost savings achieved

- Revenue uplift from dynamic pricing agents

- Reduction in DSO, inventory holding costs, or fraud losses

When it works, it’s powerful. It aligns incentives and forces vendors to care about real-world impact.

When it fails, it fails spectacularly:

- Attribution disputes (“Was it the agent or market conditions?”)

- Gaming of baselines

- Endless renegotiation when business conditions change

Outcome-based AaaS requires unusually high trust and data transparency. Most enterprises say they want it. Few are structurally ready for it.

4. Managed Autonomy (Hybrid Models)

This is where many serious deployments land, even if they’re marketed differently.

The vendor provides:

- Agents

- Continuous tuning

- Human oversight

- SLA-backed intervention

Pricing blends subscriptions, usage tiers, and service retainers. It’s messier but more honest.

This model acknowledges something uncomfortable: most enterprises are not ready to hand full autonomy to software without a safety net. And frankly, that’s reasonable.

Where AaaS Creates Real Value

Some domains are simply better suited to agent-based delivery than others. Not because they’re trendy, but because their decision loops are well-defined.

1. Logistics and Supply Chain

Dynamic routing, carrier selection, slotting decisions, and exception handling are fertile ground.

A real example: a mid-sized freight broker deployed pricing and routing agents that adjusted quotes based on capacity signals, weather, and lane performance. Human teams still handled strategic accounts, but agents managed spot quotes. Margin volatility dropped noticeably—not eliminated, just dampened. That nuance matters.

2. Finance Operations

Think reconciliation, credit policy enforcement, cash application, and collections prioritization.

Agents excel when:

- Rules are complex but bounded

- Exceptions follow patterns

- Speed matters more than perfection

They struggle with judgment-heavy edge cases, which is why human escalation paths remain essential.

3. Manufacturing and Asset Operations

Embedded agents are becoming viable for monitoring equipment health, adjusting maintenance schedules, or coordinating production changes based on demand signals—especially when latency matters.

These agents don’t “think” like humans. They optimize within constraints. That’s often enough.

So, Is the Market Ready?

Technically? Mostly yes.

Organizationally? Uneven.

Commercially? Still experimental.

AaaS will not explode the way SaaS did. It will creep, embed, and quietly replace chunks of operational work where autonomy makes sense. Some agents will fail and be rolled back. Others will become invisible infrastructure.

That’s probably how it should be.

The companies that succeed—both buyers and providers—will be the ones that resist grand narratives and focus on disciplined deployment. Clear scope. Clear accountability. Realistic autonomy.

Agent as a Service is not a destination. It’s a working arrangement. And like most working arrangements, it succeeds less because of ambition and more because of restraint.